Part I: Setting Baseline Agreements for Stewardship Behavior

Jaffe and Clyne explore four key questions in the course of these two issues:

- How does a family develop an extended family mindset and create stewards for the future family fortune?

- How do families of wealth encourage young family members to remain connected and engaged as each of them explores personal opportunities?

- What preparation is required and what opportunities exist to develop the next generation of family leaders?

- How can family elders comfortably make room for future family leaders?

And . . . they give a warning that instilling a culture of stewardship as described in these articles is not a quick fix. Making it happen requires continual, multigenerational family engagement and activity.

Please read on for Part 1.

Expectations

Enterprising families often define aspirations and roles that they expect of the rising generation and from new family members. Those statements often look like this:

- We want to fulfill our potential as an extended family by developing your trust in each other and connection to the family legacy.

- We want to see you doing things together, being engaged, and taking part in the family enterprise.

- We desire our family to sustain deep cross-generational connection, trust, and care.

- Given how much we have already achieved and the gifts we have received, we share a responsibility for how we will live and work in the future.

Successful families see it differently. They respect their children’s journeys toward self-fulfillment, but they know that the family enterprise offers a great gift as well. They want their children to take the family and the multigenerational wealth seriously. They want them to sign on as active family “citizens,” dedicated to making the family culture work and endure, even as they pursue their own paths.

Building a Culture of Stewardship

In his classic book, Stewardship: Choosing Service Over Self-Interest,1 Peter Block defines a culture style of stewardship, premised on relationships that build the common good of the wider community. Stewardship means giving everyone in the organization a true voice and ownership in how the business is run. Block defines stewardship as the spirit of partnership and service—a definition well suited for upcoming generation members who desire to serve with their voices heard and respected.

Successful families base their culture on gratitude and a sense of shared obligation to do well with what they have received. The culture is not premised on how much wealth they have, but on how they use their wealth to make a difference. In contrast to this idea is the belief that family members become “entitled” when they focus on what they have, instead of on what they are expected to contribute. They see their wealth as a prize, not as an obligation.

The central question becomes “How can a family develop a stewardship mindset and create new generations of responsible stewards?” Jaffe and Clyne’s experience shows the following:

As more people enter the family—by becoming adults or marrying in—they should be offered opportunities to learn and voluntarily agree to the family culture’s principles without feeling coerced into passive acceptance. This is an active, ongoing process of learning, accepting, and acting not just by a few, but by a substantial number of individuals in the extended family.

A Model: Phase 1 (Phases 2 and 3 will be discussed in subsequent article)

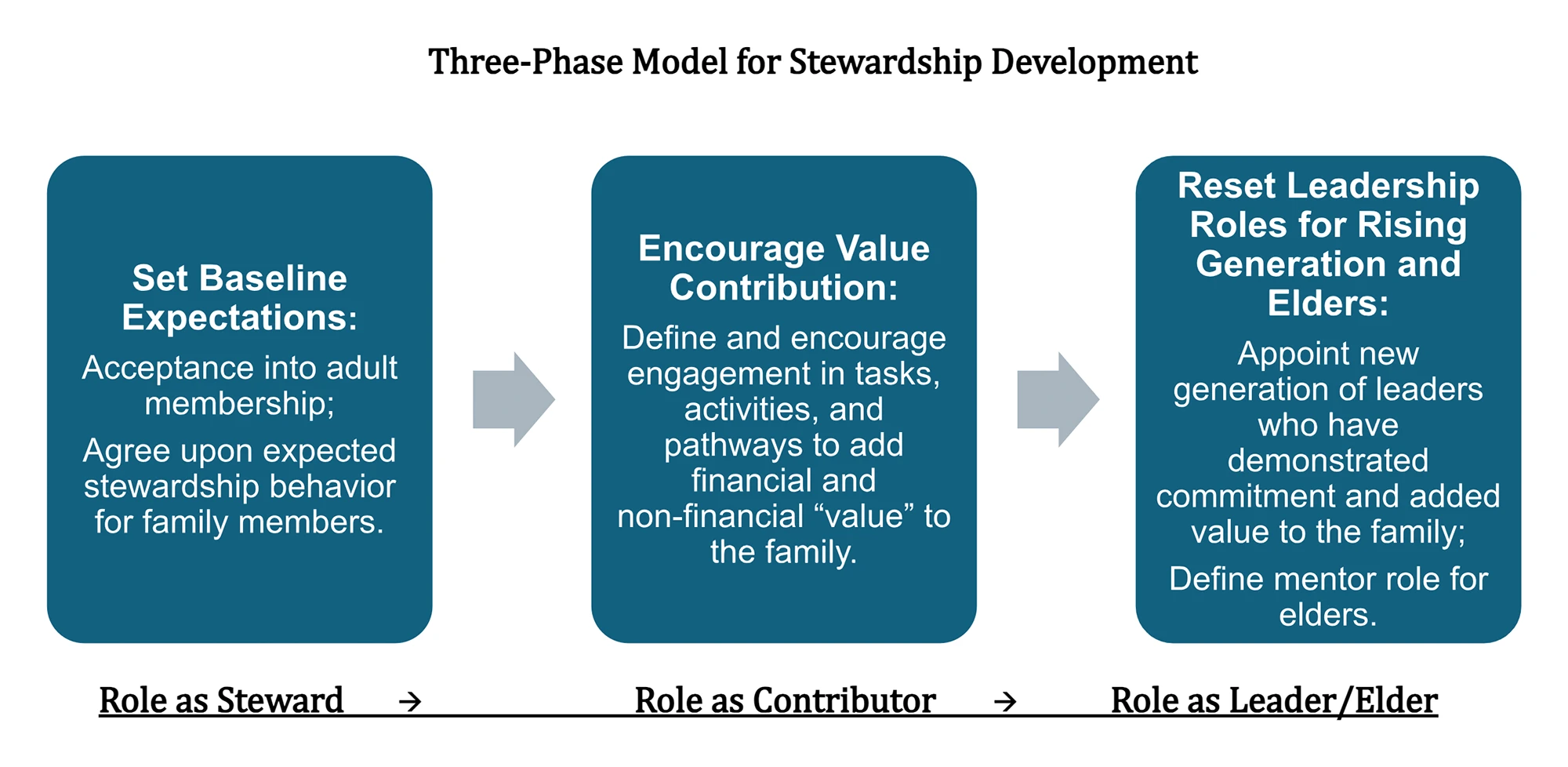

To further assist in building a culture of stewardship, the authors propose a three-phase development model, based on supporting emerging roles as a steward, a contributor, a leader, and an elder. Once young family members understand the responsibilities and qualifications of each role, they can embark on a path that builds a family stewardship culture.

Set Baseline Expectations for a Family Steward

A first step is for family members to understand what stewardship involves and knowingly commit to it, since the family culture can only be sustained if its members agree to take on its specific responsibilities. For example, new family stewards might be expected to attend an annual meeting, serve on committees, or vote on key issues. In all cases, new stewards are expected to understand the basic nature of the organization and be financially literate about the structure and nature of the business and shared assets. But they must agree to actively respect these expectations.

Since wealthy families often contain several branch households formed by each new generation, it can be useful to see these branches as a type of tribe. Tribal cultures typically contain policies and rules that govern how the tribe works. New or younger family members are expected to follow the tribe’s rules and prove themselves worthy of membership in the leadership group, i.e., the elders.

The first step in becoming an elder is to become a steward. When they ultimately become “stewards,” family members demonstrate skills and knowledge and agree to live within the culture. Becoming a steward may be celebrated by a ceremony welcoming individuals into tribal citizenship. At this time, they may be asked to demonstrate their knowledge and skill in some visible way and to pledge to adhere to the values, rules, and expectations of the group. This all-family celebration is one way to answer the concern of parents regarding how to create responsible offspring. If their offspring are honored and accepted and the community spells out what is expected of them as stewards, then it is clear how they are being called to behave and why. In effect, this transfers the responsibility for their adult behavior from their parents to the whole tribe.

Some baseline statements specify behaviors and capabilities expected of a newly adult or married-in family member before becoming a fully accepted steward and enjoying the benefits of the family’s wealth. Such a statement often includes the following:

- Understand and agree to live by the family’s shared values.

- Attend and be active in family events and activities.

- Adhere to family rules for communication, personal relationships, and social media.

- Understand the family’s business, financial, trust, and governance structure.

- Create and follow a personal plan to develop skills that could make a positive difference.

Resources for Learning Together

For these behaviors and actions to be fully acted upon and realized, the family would provide resources for active learning. These resources can be workshops and learning sessions, stored online, for each area listed. Other resources might be internships and training programs or internal briefings about the nature of the family assets and how they are structured.

By learning together, the family gets to know each other and can consider questions, concerns, and reservations before coming to agreement. With this process, the family commits to active implementation of stewardship behaviors. It performs the critical task of initiating people into the family culture and celebrating their membership in what is an exclusive club.

The next article, Part 2, will include a discussion of Phases 2 and 3 of the model.

Reference

1 Block, Peter. Stewardship: Choosing Service Over Self-Interest, 2nd ed. San Francisco: Berrett-Kohler, 2013.