Introduction

Both the word and the concept of the “generation” are fundamental and deeply embedded in family business studies and among scholars.

Christina Lubinski and William B. Gartner, the two authors of this study, argue that the concept of “generation” in family business studies has mainly been addressed from the perspective of lineage, role assignment, biological transmission, or succession in terms of transfer of wealth from one generation to another. The focus has been primarily on family relations rather than the societal or cultural dimension which impacts and colors the history and development of family businesses.

This study aims to fill this gap in the research and to inform family businesses and practitioners of its implications. The conceptual framework’s starting point are the ideas of the German sociologist Karl Mannheim (1923/1952, pp.281-282), who argues that generation is “about the human experience of belonging to a generation,” and the French historian Paul Ricœur (1988), who suggests that “the time of belonging becomes enacted in the historical narrative.” For Ricœur, generational transition is also an “established form of speaking about and ordering the past” which embeds in its narrative the shared social and cultural context through time.

This research investigates the word “generation,” aiming to understand rhetorical history processes through families’ own narratives and an examination of its semantic meaning, which can shed light upon family dynamics and the societal environment of the time. The focus is on historical phenomena. Rhetorical history addresses how family business actors “use the construct of generation in narratives” and how these narratives and their lived experiences can link their past, present, and future trajectory. This approach can also emphasize “the strategic use of the past” (Suddaby et al., 2010) and can help in shaping future organizational strategies.

Methodology

This study is a form of ethnography, mainly based on a case study and the reading of historical archive sources in order to shed light on organizational dynamics and memory in a family business, namely the Bagel company, a German publishing and printing business, founded in 1801 and currently led by the seventh generation. The family made available its private archive in which many narratives, both about the family and the business, have been meticulously collected through the years, documenting a long history. Before visiting their archives, the authors read other printed materials from the local town archives. One of the authors analyzed the Bagel Group’s archival material and its in-house magazine, and also interviewed the present CEO and his daughter, the expected successor. Three specific episodes in the life of the family business were taken into consideration. The historical and contextual dimension guided the interpretation of the data. Many examples from the narrative are offered in the paper as explanations and support of the concepts and findings described below.

Findings

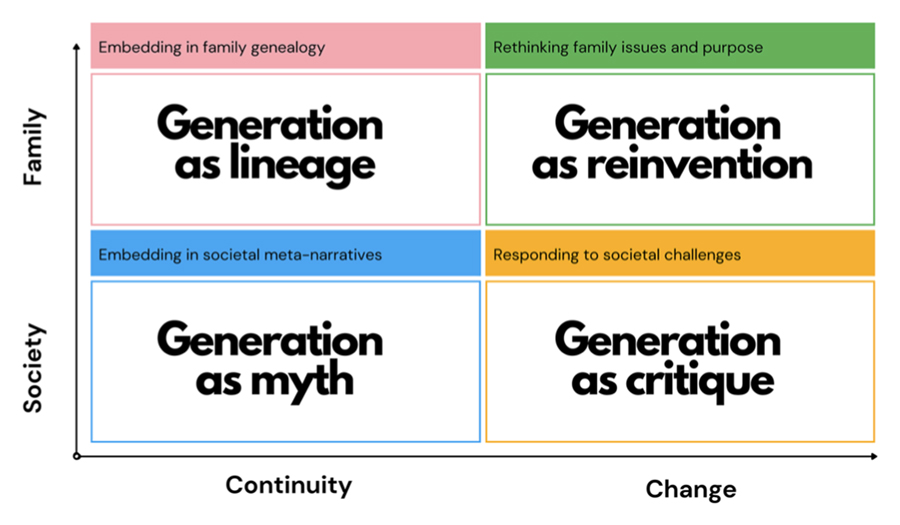

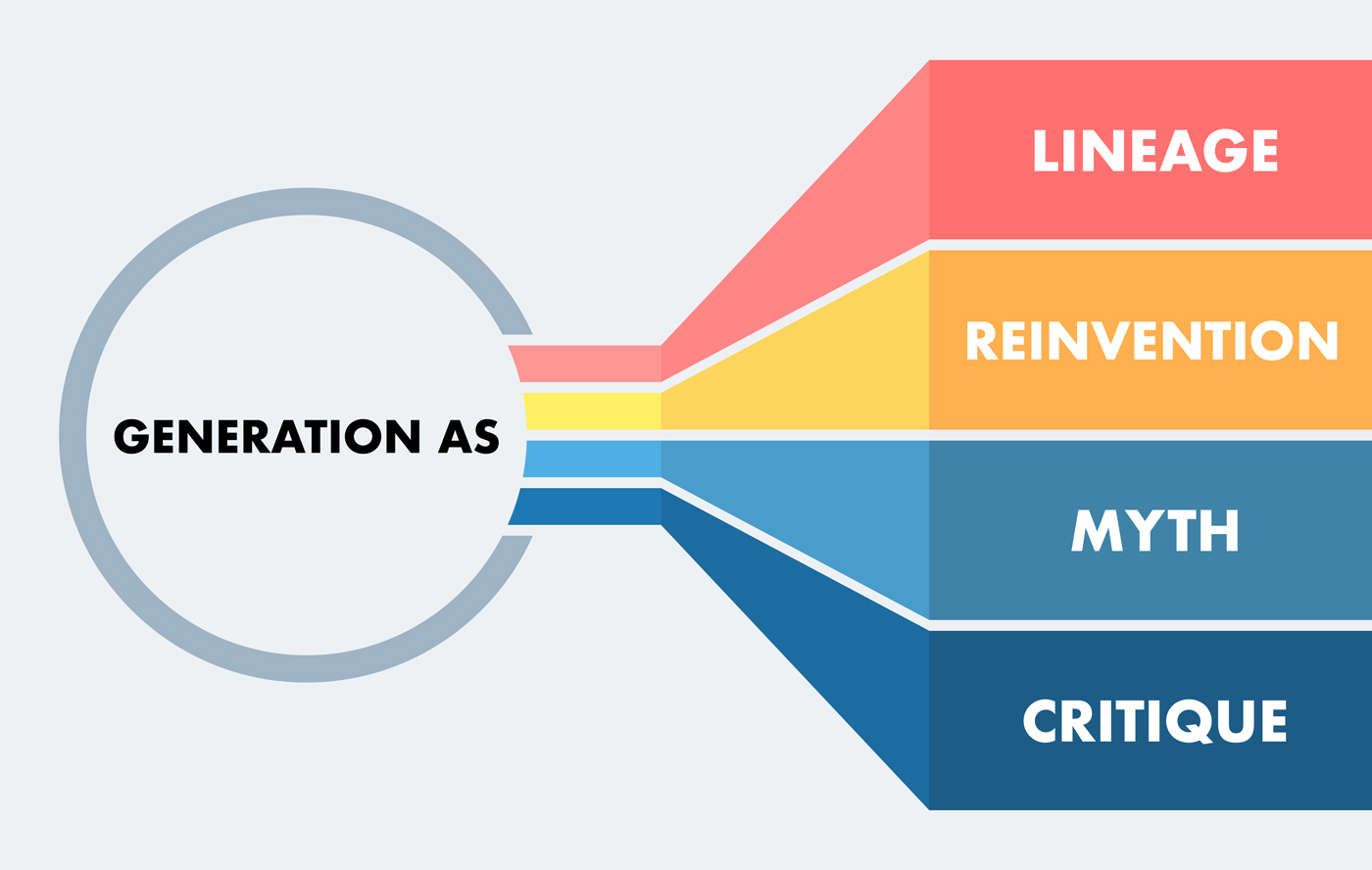

Four different types of usage of the word “generation” were identified within the storytelling in the archives. A definite time span (from post-WWII until 1977) and specific episodes or events were taken into consideration (for example, commemorative books, obituaries, Christmas speeches, etc.). Two usages of the word “generation” focus on the connection between past, present, and future, from the perspective of continuity over time—Generation as Lineage (Continuity in/of Family) and Generation as Myth (Continuity in/of Society), while the other two position the narrator in his/her own time, emphasizing change—Generation as Reinvention (Change in/of Family) and Generation as Critique (Change in/of Society).

Generation as Lineage (Continuity in/of Family)

“Generation” here is intended as genealogy, focusing on the way family lineage provides structure to the past over time. Continuity over time is an important value, manifested for example through expressing gratitude to ancestors and engaging in imaginary conversations with them, in some cases looking for an endorsement. The past can explain the present and forecast the future in an imagined linear path with the family lineage as a guide.

Generation as Myth (Continuity in/of Society)

The idea of “Generation as myth” also emphasizes the dimension of continuity over time, but with this usage, a connection is also made to the societal context in which the family business is located and was established. This can lead to the development of mythical stories, for example if the context or the time of creation of the company coincided with a particular historical, social, political, or technological moment (the Bagel printing company opened a new building on an anniversary of Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of printing). This can enhance continuity and a present timeless, legendary image of the firm.

Sidebar

Generation as Reinvention (Change in/of Family)

“Generation as reinvention” underlines change in the narrator’s own time; it considers the changes in society and expresses the need to rethink the family enterprise’s issues and purpose. Each new generation contributes its own point of view and narrative. For example, “savior” anecdotes, stories of how individuals saved the business through reinvention or deviating from tradition, are often linked to the challenges of the time. This narrative is often connected to “age-balanced leadership,” in which a member of the older generation can take up a role of advisor and bearer of tradition, while the new generation comes in with its enthusiasm and desire to make an impact through innovation. Although this is not always the case, this type of partnership can help to come to terms with the tension between “tradition and innovation.”

Generation as Critique (Change in/of Society)

Here too the focus is change, but in a broad societal context requiring innovation. In times of disruption, the firm must engage with the new challenges of that period. Interestingly, change in the usage of the word “generation” can be spotted in the way in which some anecdotes that contain mythical events or specific turning points can lose their meaning or the context can be forgotten, as the moral of the story evolves to become more connected with contemporary challenges.

Implications

Implications for practitioners

The model of the Four Uses of Generation in Family Business Narratives (Table 1) has the following implications for family enterprise advisors:

- This model can be helpful for practitioners both in preparing for and in undertaking any advisory work. Practitioners should consider that families and businesses are embedded in the current cultural and societal context and develop through time, and this phenomenon impacts the narrative and actions of the actors involved. A family enterprise’s multiple generational narratives can also impact leadership, and understanding their influence can clarify what type of leadership is necessary at a specific time.

- Enabling clients to look at the concept of generation in the process of storytelling can support family business members in learning about their history, gaining a new self-awareness and capacity to reflect on events.

- This model can serve as a tool for practitioners in their work with family enterprises to discuss legacy and the utility of looking at their families’ stories through generations, thus helping both family members and key non-family employees to position themselves generationally and consider their roles within the time and context in which they operate. Considering various rhetorical uses of “generation” can promote understanding of how different past generations have taken up their entrepreneurial roles and awareness of how new generations can reinvent these roles in their own ways.

Implications for family firms

This history-based model can also assist family firms in the following ways:

- Supporting family firm members to make sense of and reflect on their family and business, and to understand the deeper meaning of their narratives, including anecdotes, stories, rituals, artifacts, etc.

- Preventing family firm members from getting stuck in one historical narrative which may have become outdated by recognizing the different meanings of the word “generation” and its impact on storytelling both individually and socially, especially when confronted with the tension between tradition and innovation.

- Helping family businesses to address issues concerning their specific legacy and to understand that legacy, although valuable in terms of continuity, can be “changed and dropped over time.”

- Fostering a more useful consideration of the past by integrating it into the present dynamics and thus helping to shape the future.

Implications for applied research

- This study’s area of investigation is of one specific company, based in Germany, with its social and cultural identity. As the authors suggest, it would be important to understand how the different cultural contexts in which a company is located affect the usage and structuring of the word “generation,” and thus the related types of storytelling and how the family enterprise members debate legacy and the past.

- Future research should also address more “triggering events”—e.g., times of crisis, disruptions, or turning points that can create new challenges and opportunities and shape a new phase in an organization, promoting new entrepreneurial roles for the new generation members. This work could offer new insights on how to rethink and integrate a family’s past, present, and future.

References

Lubinski, C., & Gartner, W. B. (2023). Talking About (My) Generation: The Use of Generation as Rhetorical History in Family Business. Family Business Review, 36 (1), 119-142.

Mannheim, K. (1952/1923) The problem of generations. In P. Kecskemeti (Ed.) Essays on Sociology of knowledge. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul (Original work published in 1952) (pp. 276-320).

Ricœur, P. (1988) Time and Narrative, Volume 3. University of Chicago Press.

Suddaby, R., Foster, W.M. and Quinn Trank, C. (2010), “Rhetorical history as a source of competitive advantage. Advances in Strategic Management, 27, pp. 242-278