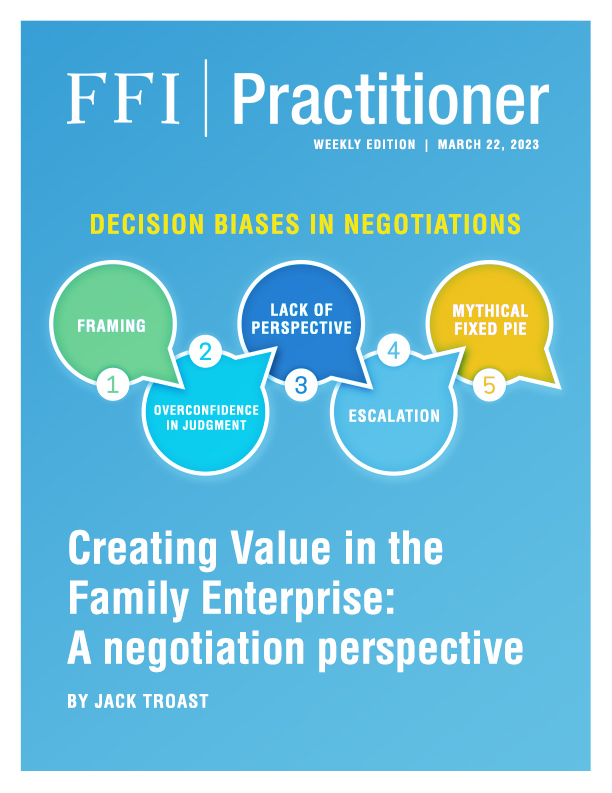

The field of family enterprise advising has identified key challenges that must be addressed by families in business in order to achieve success and continuity. These challenges include succession planning, effective communication, navigating value conflicts between the business system and the family system, and the need to professionalize management functions as the business grows, to name a few. Each of these challenges includes decisions among family members that require engaged communication and, at times, negotiation.

In their book Judgment in Managerial Decision Making,1 authors Max Bazerman and Don Moore suggest that joint decisions with different perspectives give rise to negotiation. The organizational context for these negotiations is often complex, and decision-making is susceptible to systematic errors in judgment. Negotiators often make choices or reach agreements based on incomplete information or encounter other forms of bias that prevent them from making optimal decisions. Why does this happen and how can family enterprise consultants help their clients improve their decision-making?

1) Framing

Research indicates that people generally favor outcomes framed as “gains” over those labeled as “losses” even if they generate identical outcomes. In experiments conducted by economists and psychologists there is very clear bias for choosing a benefit or gain when framed as such.2 Mediators and family enterprise advisors should be aware of this bias when working with clients and seek to frame potential outcomes as mutually beneficial gains when possible.3

2) Overconfidence in Judgment

Many decision makers are prone to overconfidence when looking at options. In his bestselling book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman attributes this overconfidence to a tendency on our part to rely on intuition and instinct or “System 1” thinking.4 We tend to rely too heavily on the evidence most easily recalled, often ignoring other information when making decisions. Family enterprise advisors can work with their clients, particularly those threatening or engaged in litigation, to remind them that while their legal advice may be sound, they should consider a broad range of possible outcomes and recognize a bias toward overconfidence.

3) Lack of Perspective

Throughout Judgment in Managerial Decision Making, Bazerman and Moore offer multiple research studies explaining why we tend to favor our interpretations of a dispute and support our perspective in contrast to others. Many family enterprise advisors encourage family members to take the perspective of others in a decision or dispute. Conflict research identified by social psychologist Dean Pruitt and followed by others5 suggests that role reversal increases the likelihood of a negotiated resolution. This is also an essential tool among mediators in their work. In the negotiation classic Getting to Yes, Roger Fisher and William Ury offer their powerful advice to separate “positions” (stated goals) from “interests” (actual goals) and to focus on the other parties’ “interests” to find common ground in a negotiation.6

4) Escalation

Research across disciplines in psychology, economics, and political science shows that escalation is a critical decision bias. This research generally shows that after an unsuccessful financial outcome, parties will often “double down” on their financial exposure, escalating the conflict without a rational basis. Furthermore, one party may reactively devalue concessions made by another party in a negotiation, out of suspicion of the conceding party’s motives. Consultants will often see family members increase their commitment to their “position” in a dispute, and as time progresses and conflict escalates, it becomes more difficult to retreat from their public position. Mediators and advisors can serve their clients by muting efforts to escalate conflicts, particularly in a public fashion.

5) Mythical Fixed Pie

Mediators and negotiators often speak in terms of the differences between distributive and integrative bargaining. In the case of distributive bargaining, the parties see the outcome as strictly a matter of dividing what Fisher and Ury describe as a “fixed pie,” particularly when they are disputing a fixed sum of money or the value of an asset. This would generally apply to salary, or the distributive share of an estate or a family business. The integrative model of bargaining seeks to find mutually beneficial trade-offs that look at a larger set of distributive outcomes. Research by Bazerman and others7 has shown that most negotiators are biased in favor of distributive outcomes, i.e., “Your gain is my loss.” Family enterprise advisors will benefit their clients by breaking down this false assumption and assisting them in looking for mutually beneficial trades.

A few years ago, I worked with a family that was locked into competing positions in a dispute over jointly held land. A developer was ready to acquire the property and was offering the family the highest financial payoff. Some in the family had varied interests in the property, including working the land or donating the property to an interested conservation group, seeing the worth of the property in terms outside its monetary value. As a part of a multidisciplinary team, we helped the family break from the assumption and inherent bias that the land had only a distributive value to be shared equally. We assisted the family and their counsel to see the benefit in moving from a win-lose scenario to a mutually beneficial outcome. Over a series of meetings, the siblings saw the alternative benefits beyond the financial benefits offered by the highest bidder.

Negotiation experts, behavioral economists, and mediators have been looking at the impact of decision bias in an effort to achieve better outcomes for decision makers. This perspective can also encourage family enterprise advisors to look at the impact of cognitive bias on their client situations.

References

1 Bazerman, M.H., & Moore, D.A. (2012). Judgment in Managerial Decision Making (8th ed.). Wiley.

2 Bazerman, M.H. (1983). Negotiator Judgement: A critical look at the rationality assumption. American Behavioral Scientist 27(2), 211-228; Thaler, R. (1980). Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 1(1), 39-80; Tversky A., and Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 211(4481), 453-463.

3 Bazerman, M.H and Neale, M.A (1983). Heuristics in Negotiation: Limitations in dispute resolution effectiveness. In M.H. Bazerman and R.J Lewicki (Eds.), Negotiating in Organizations. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage

4 Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

5 See Pruitt, D.G. (1981). Negotiation Behavior. Academic Press; Zubek, J. M., Pruitt, D. G., Peirce, R. S., McGillicuddy, N. B., & Syna, H. (1992). Disputant and mediator behaviors affecting short-term success in mediation. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 36(3), 546–572.

6 Fisher, R., Ury, W., & Patton, B. (2011). Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In (3rd ed.). Penguin Publishing Group.

7 Bazerman, M. H., Magliozzi, T., & Neale, M. A. (1985). Integrative bargaining in a competitive market. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 35(3), 294–313; Bazerman and Neale (1983). Heuristics in Negotiation; Thompson, L., & Hastie, R. (1990). Social perception in negotiation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 47(1), 98–123.

8 Hoffman, A.J., Riley, H.C., Troast, J.G., & Bazerman, M.H. (2002). Cognitive and Institutional Barriers to New Forms of Cooperation on Environmental Protection, American Behavioral Scientist, 45(5), 820-845; Troast, J., Hoffman, A., Riley, H., and Bazerman, M.H. (2002). Institutions as barriers and enablers to negotiated agreements: Institutional entrepreneurship and the Plum Creek Habitat Conservation Plan. In A. Hoffman and M. Ventresca (Eds.) Organizations, Policy and the Natural Environment: Institutional and Strategic Perspectives (pp. 235-261). Stanford University Press.