Generational transfers are a unique experience for every business family.

However, we have been able to identify five different models of generational transfer, analyzing how the process developed in a sample of 100 Argentine and Paraguayan companies with whom we worked as consultants.

Each of these models has its own logic, involves values that differentiate it from other models, and conditions for success that we must identify in order to collaborate using the most efficient means possible in every case.

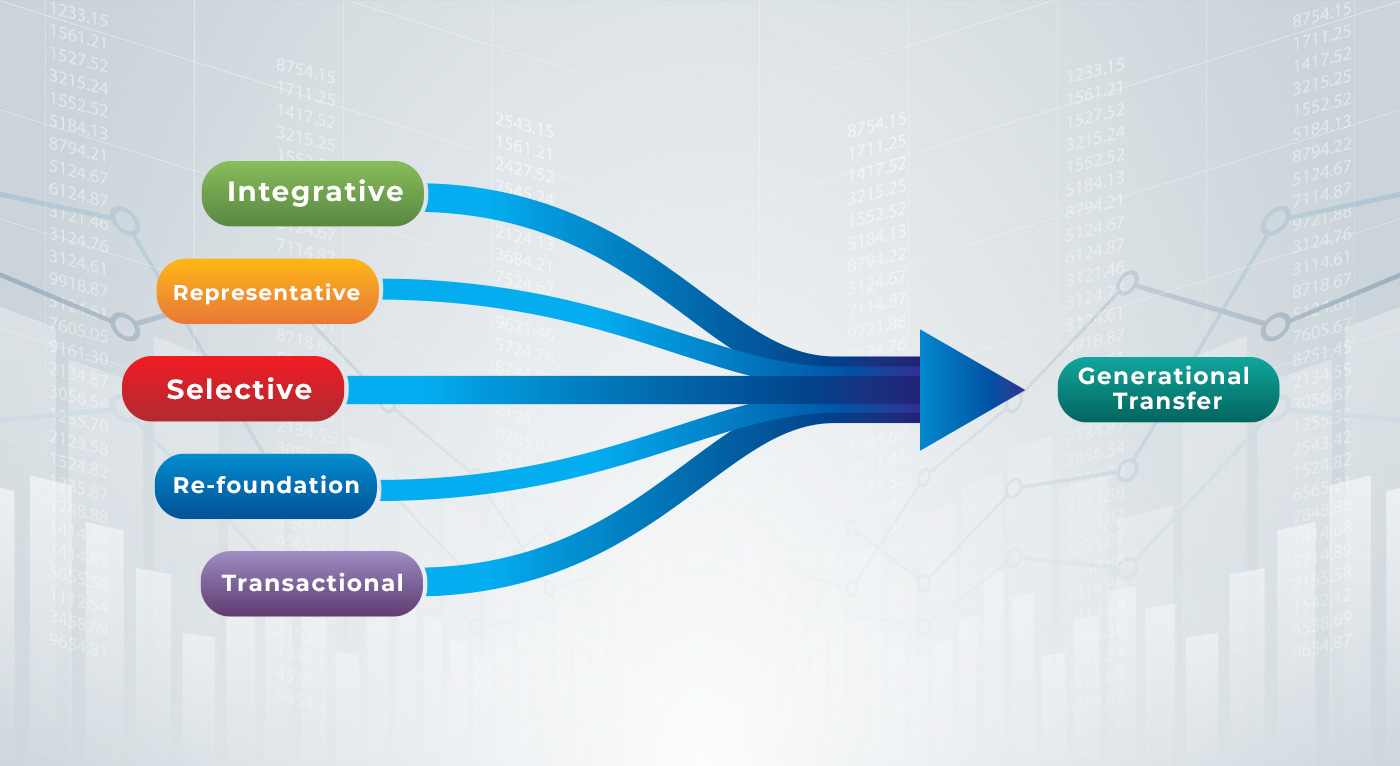

What are those models? We have called them:

- Integrative

- Representative

- Selective

- Re-foundation

- Transactional

INTEGRATIVE MODEL

The main succession axis belongs to the biological family.

All children must be heirs of capital, and the differentiation between them will be based on their respective roles within the family enterprise: there will be those who work, those who manage, those who run the company, and there will be shareholders who will not actively participate in the company’s development whatsoever and will simply receive their benefits as shareholders.

This model responds to the vision of creating a family business that transcends generations, and that continues to grow as an economic family group, reinvesting its surplus for the expansion of its current business or the foundation of new endeavors.

Therefore, awareness of the privilege of belonging to the family business is the starting point for cementing emotional and economic ties in a framework of collaboration and mutual respect.

Values such as equality, solidarity, mutual understanding, task-collaboration, respect for the freedom to choose one’s career, the composition of interests—all belong to a lifelong learning process.

REPRESENTATIVE MODEL

Similar to the integrative model, family businesses that use the representative model also provide for the successors’ ownership status due to their family lineage. However, their access to corporate decision-making is organized and regulated, not in an undifferentiated form as in the integrative system, but as members of their respective family lineages.

This model (usually introduced when the second generation already plans to integrate their children or later generations) tends to privilege the order of corporate participation, since shareholders do not directly participate in an assembly to defend his or her own interests, but instead must be appointed by members of his family lineage to perform that function or must delegate the representation of his or her interests to another person.

This system works through such instruments as the creation of share blocks, the company by-laws, or trust documents.

In some ways, the representative system exists as a higher, more consolidated stage of the integrative system.

This model is intended to make the business more durable. Generally, businesses expand beyond the original business, and the patrimonial benefit of belonging to the family business is privileged. At the same time, the representative model tends to professionalize management.

To the extent that the family is larger when the third or subsequent generations are involved, the representative system makes it possible to consolidate some rules for the for the benefit of the business group. By electing one representative for each lineage of shareholders, mass assemblies are not required to make every ownership decision.

This makes it possible to raise the level of discussions among these representatives, since it is possible to establish eligibility requirements to become an ownership representative based on technical or academic backgrounds and adherence to the family values.

Additionally, situations are avoided that could jeopardize family peace. For example, perhaps a member of one family branch adheres to his cousin’s position and votes with him or her, thereby harming that person’s own brothers or sisters. A restriction on the sale of shares in companies to the extended family or to third parties is also often established, with priority being given to members of the same family lineage. This model often admits the participation of in-laws as company shareholders, but limits their participation in management bodies through the management of shares.

SELECTIVE MODEL

In this model, the current owner chooses his or her successors, who are not necessarily members of the next generation. This model gives successors a place in the company (while, in many cases, excludes others) until at some point it grants them increasingly greater corporate participation until they have acquired full authority and participation.

In this model, the dominant values are the company’s continuity. The effort and the commitment of some successors take precedence over concepts such as family equality or unity.

Consequently, the company’s survival is not the result of the desire and action of a group of people with different roles, but is due to the effort of a specific successor (sometimes a group of siblings, but not all of them), described in the motto, “Out with the old, in with the new.”

Sidebar

What factors typically lead to family utilizing the selective model of succession?

- The founder’s decision to choose a unique successor in the company.

- The lack of affectio societatis between siblings, or the lack of interest from some of them.

- The active behavior of someone who, over the years, strives to hegemonize leadership, especially that of the company’s ownership.

RE-FOUNDATION MODEL

One or more members of the next generation (via blood or marriage) take charge of the management, and more or less simultaneously, of the company’s ownership. They expand the business in such a way that, over time, the question arises of whether they are a successor generation or, given the growth that they had generated, they are part of the founding generation, which can cause significant confusion among the members of the family business.

In many cases this model develops (albeit unconsciously) when the company is going through a severe crisis or other contingency (preventive competition, fire, abrupt change of market conditions, loss of licenses, etc.), which leads to the next generation to “reinvent” or reorganize what they had received.

Once the next generation is successful at this task, the successor usually desires recognition.

But the family business’s other members often do not share the view that the company was saved or had extraordinary growth thanks to the contribution of a select few family members.

Therefore, this model is often a source of conflict. The conditions for each member’s participation were not specified in the immediate struggle to keep stay in business, or during dramatic growth to the company.

It is very likely that, when a consultant intervenes in a situation in which a re-foundation was passed, it becomes necessary for him or her to articulate mechanisms to unify the company’s future vision, especially to reach a shared version of the past.

TRANSACTIONAL MODEL

The older generation sells their stake in the company to all or a part of the next generation, who pay a sum within a specified period or through annuity, but in return, they get property, responsibility, and the integral management of the company. Use of this model can, at times, lead to the buyer feeling like, or appearing to be, the founder, as if the transaction has taken place with a third party outside the family.

In these cases, the dominant values are the seller’s desire for economic tranquility and the belief that the buyers’ economic commitment will guarantee a dedicated and responsible management, which will in turn give the company continuity.

CONCLUSIONS FOR ACTION

Each generational transfer model responds to a foundation of origin, and each brings about particular consequences.

Thus, the integrative and representative models are typical of families that have a dream of creating a multi-generational legacy through the company. The selective and transactional models respond to the belief in individual effort and differentiation between family members according to their participation in the business, while the re-foundation model responds, normally, to a contingency that was not processed harmoniously in the family business.

Understanding the conditions for the operation of each model, its benefits and its potential risks, allows us as consultants to provide each family business and each business family with the most effective tools so that they can successfully go through the complex generational transfer process.

Leonardo J. Glikin is a lawyer and a consultant in Estate Planning and Succession for family businesses. He is the founder and president of CAPS Consultores, head of the Family Business Program at the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, and the author of Pensar la Herencia (Emecé, 1995, CAPS Ediciones 2000) Matrimonio y Patrimonio (Emecé, 1999) Exiting, el arte de dejar la empresa sin dejar la vida (Errepar, 2012, Aretea Editions 2014), Los hermanos en la empresa de familia (Aretea Editions, 2014) Iguales y Diferentes, los espacios de la mujer en la empresa de familia (Aretea Ediciones, 2015), and Manual de Planificación Sucesoria para Asesores de Seguros de Vida (Aretea Ediciones, 2016). He is also the director of the monthly e-newsletter Business and Family Issues.