Such was the case with the Bray family (not their real name), owners of a supermarket chain in Colombia. The oldest of the three brothers, Santiago, approached me to work with his family. He assumed his role of eldest brother with great pride and determination. Once the meeting started, I began to notice how, little by little, his body language started betraying his posture of self-confidence. When the time was right, I asked him to tell me more about his family. Below is an excerpt from our exchange:

Guillermo: Why are you ashamed?

Santiago: Because all the families you have worked with must be happy and functional to be able to have successful companies.

Guillermo: What makes you think that? Who told you that your family is dysfunctional?

Santiago: Nobody. I deduce it. We have a particular way of relating. My family is not a normal one. I think that’s why sometimes I feel we’re not a happy family. And we should be.

Functional and Dysfunctional Families

Santiago oversimplified the complex relationships within his family by labeling them as “dysfunctional.” I have found that when a member diagnoses his or her family with this term, it tends to be more associated with the myths that society has created around the concept of dysfunctionality in general. A dysfunctional family is one in which conflicts, misbehavior, or abuse occur continuously and regularly, creating for their members a “normality” of a lack of structure and emotional support. On the other hand, a functional family is a family where hierarchy, norms, and limits offer a secure environment for a nourishing development of their members.1

How should a family enterprise advisor assess the dysfunctionality of a family? It’s hard to say in a technical way. Only a licensed specialist in mental health disciplines can determine whether a family is in a stage of permanent pathological imbalance or breakdown. And even among experts, there can still be debate.

Sidebar

By: Guillermo Salazar

This week’s contributor, FFI Fellow Guillermo Salazar, explores the relationship between the hero archetype and storytelling in family enterprises.

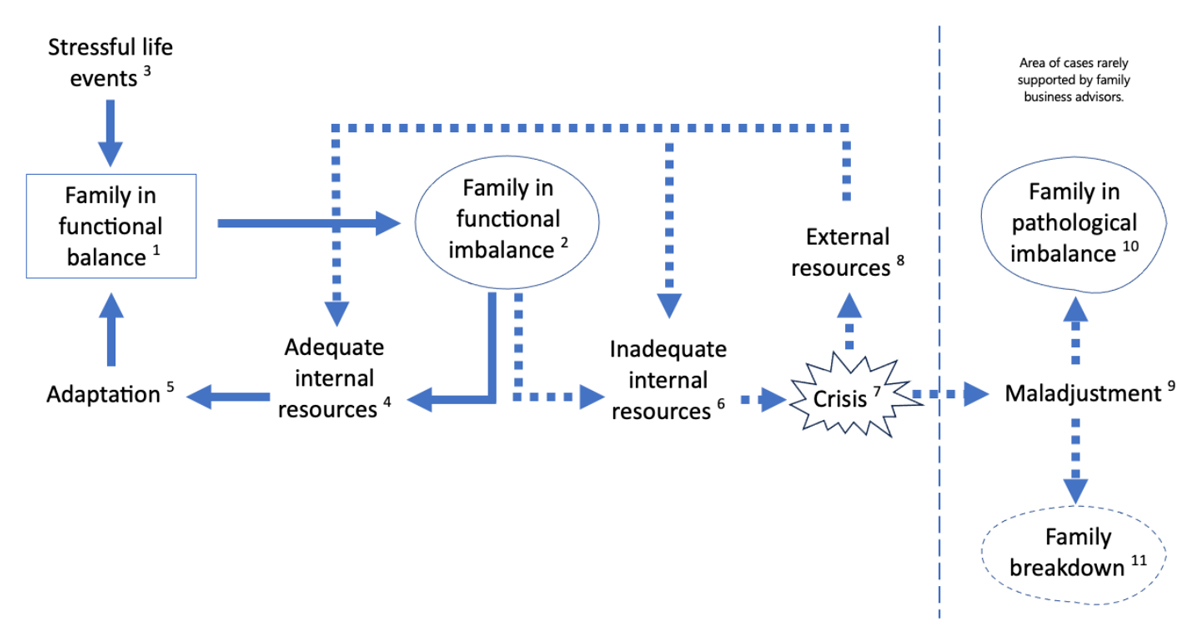

The Family Function Cycle

The Family Function Cycle model can help advisors understand how a family may address a crisis. The diagram (see figure) describes how a family in functional balance (1) can transition to a functional imbalance (2), as a consequence of unexpected stressful life events (3), including business cycles and transitions, accidents, migrations, diseases, economic downturns, etc. With adequate internal resources (4), such as conversations between their members or activities that strengthen family unity, a family can find ways to adapt (5) to the new environment and recover their functional balance (1). However, if these internal resources are inadequate (6), it can lead the family to a crisis (7).

Source: Own elaboration, based on Gabriel Smilkstein (1980) and Ana Pérez (2020).

The Anna Karenina Principle

There is a phrase that has become popular among those who have devoted themselves to studying families: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” a phrase that belongs to Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy. In my experience, functional families that are able to fully meet the happiness requirements of their members are rare, although some families with functional characteristics in their relationships help develop the individuals’ happiness and are perceived from the outside as a happy group.

Let’s not fool ourselves: we can’t always be happy. We experience frustrations and unhappy conditions routinely in life. Happiness will always be a personal decision, not a collective quality.

Everybody’s Fine

Families often tend to deny or hide crises and show others a reality of apparent happiness. Santiago brought to his interview a predisposition to justify behaviors or circumstances that he did not want to accept but, in fact, needed to be addressed and probably changed. When a client begins to describe his family with these words or describes himself by saying, “I am special,” it is possible that he or she intends to make a minimum effort for change and may want the consultant to do the work for them.

The beloved 1990 film Stanno Tutti Bene, starring Marcello Mastroianni, tells the story of a father who travels throughout Italy to visit his disbanded progeny, finally bringing a report of the situation to his beloved wife. All the secrets and embarrassing situations that children wish to hide from their parents are naively disguised, leaving viewers with the uncomfortable responsibility of sharing the secret of the main characters, who want at all costs to preserve the honorable façade of the family. I recommended this film to Santiago as an example for understanding functionality and happiness. Fortunately, after a few sessions working with his family, I was able to help him reframe most of his initial perceptions about the functionality of his family.

The path to happiness will always depend on individual decisions. Having a family creates a co-responsibility or a two-way street: one family member can make demands of others to help increase his or her happiness but must also expect other family members to make similar demands of him or her. Sometimes, the best recommendation for family enterprise clients may be to “be honest with yourself and among yourselves.”

Bibliography

Diamond, J. (1999). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W. W. Norton & Company.

Minuchin, S. & Fishman, C. (1981). Family Therapy Techniques. Harvard University Press.

Pérez, A. & Sharma, M. (2020). “Historical and Recent Models in Systemic Family Therapy.” In Superior Course of Consultants of Family Businesses (Curso superior para consultores de empresa familiar). Nexia Institute.

Smilkstein, G. (1980). “The Cycle of Family Function: A Conceptual Model for Family Medicine.” The Journal of Family Practice, 11(2), 223-232.

Whitaker, C. & Bumberry, W. (1988). Dancing with the Family: A Symbolic-Experiential Approach. Routledge.